November, 2018

Fascination of Black Orchids:

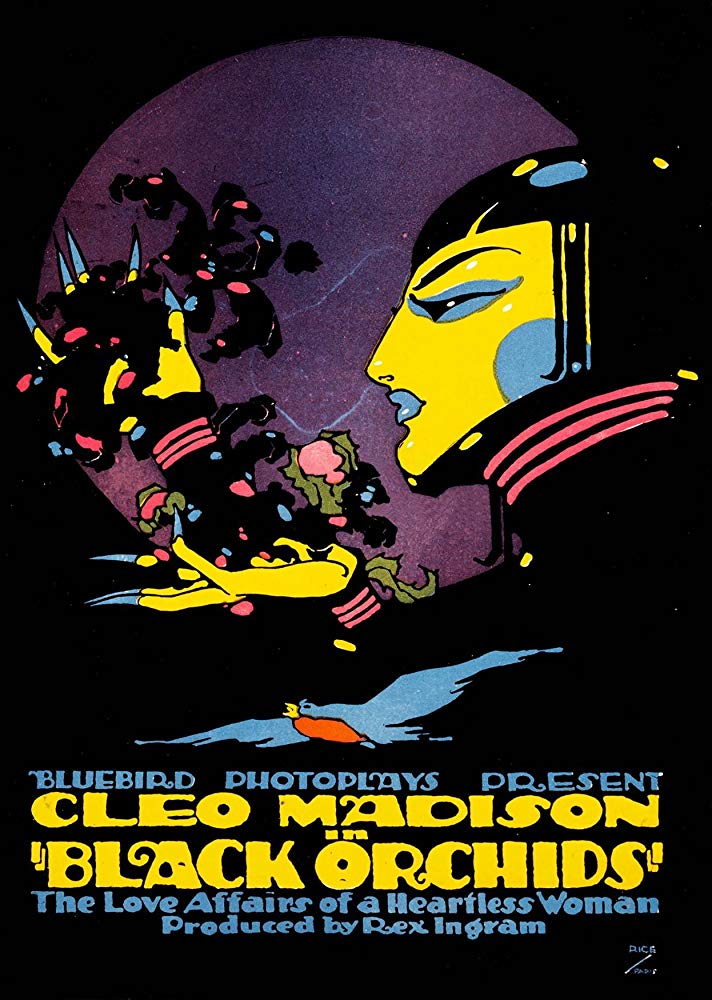

Why black orchids? Perhaps it is the association of the exotic and the mysterious, something that evokes dark recesses of the human condition, both fascinating and terrifying? In the popular media, the first example may have been the silent film Black Orchids that appeared in 1917. The film is apparently lost — mercifully, if we can judge from the lurid synopsis that survives — but a stylish lobby poster remains. As far as is known, the black orchids in question only appear in what must have been a dim, grainy film, when the evil temptress Zoraida (Fred Clarke, are you listening? How about naming one of your black orchids after this character?) places them on the grave of her husband the Marquis, who, as it turns out, is not actually dead. So, these black orchids seem to have been irrelevant to the plot, though symbolic of something evil or even depraved.But wait! There's even more about Black Orchids !

Black Orchids, synopsis: Marie, the daughter of novelist Emile De Severac, is engaged to famous artist George Renoir. Because Marie becomes very flirtatious with other men while she is on vacation from her convent school, her father relates the plot of his unpublished novel, Black Orchids, in which Zoraida, the protagonist, seduces many men. Sebastian De Maupin, whose son Ivan is Zoraida's current lover, desires her himself and thus arranges for Ivan to go to war. When Zoraida then dallies with the handsome Marquis De Chantal she enrages De Maupin, who tries to poison the marquis, but is himself killed when Zoraida exchanges the lethal cup. After Ivan returns from battle, he and Zoraida renew their affair, thus precipitating a duel between himself and De Chantal which ends when Ivan seemingly slays his rival. Ivan and Zoraida then go to a castle which De Chantal has bequeathed to her. Although De Chantal has been fatally wounded, he lives long enough to go to the castle and seal the lovers into an airless death chamber. After the story is complete, Marie resolves to pursue a different course in life. (AFI web site)

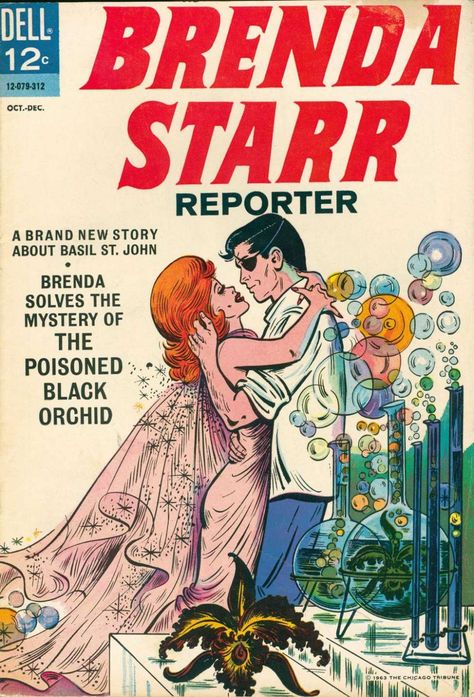

Black orchids were a central part of the story of the comic strip heroine Brenda Starr, resourceful and fearless newspaper reporter, struggling to be taken seriously by her male colleagues. The strip first appeared in 1940 and ran until 2011 (under different authors after 1985). Something of an overachiever, Brenda was always the reporter who managed to get the most sensational stories, frequently at great personal peril. Along the way, she chanced to fall madly in love with a dashing Basil St. John, her "mystery man". But he was afflicted with some unspeakable, incurable disease that could only be held at bay with a serum derived from "black orchids" from the Amazon jungle, and so he kept disappearing on what today would be called eco-travels. These black orchids look a lot like a large Cattleya, perhaps something like C. maxima. He spent a lot of time in a jungle laboratory preparing his "serum". Countless orchid fanciers probably wanted to go with him, your web master among them.

Dale Messick (1906-2005), creator of Brenda Starr, Basil St. John, and his black orchids, was herself a pioneer in a field then reserved for men. Somehow, she came to resemble her own creation. Art resembles life and life resembles art. As for Brenda, she found her way into comic books and films, but, as far as we know, never made it onto Broadway.

More recently, black orchids appeared both as a plot device and in real life, in the form of a sort of orchid documentary, The Judge, the Hunter, the Thief, and the Black Orchid (2012), drawn from orchid-related episodes that came to the attention of the film-maker Rich Walton. Among his subjects was our friend Fred Clarke of Sunset Valley Orchids, and his real black orchids. A review in the Long Beach Post (August 9, 2012) describes Fred as "an orchid hybridizer, one of a dying breed", but, fortunately for us and for the future of orchid hybrids, Fred and many other orchid breeders are still with us. We talk with them every month at our meetings, and at shows and sales throughout the year! The lurid ideas associated with black orchids (and perhaps also with orchid fascination gone wild) apparently got the better of the reviewer.

The reviewer also reports that Walton found "[orchid] societies themselves are not nearly as clandestine as one might think"! Evidently the black orchids are still inflaming the imaginations of newspaper reporters. For us, it is more a matter of trying to grow these orchids well.

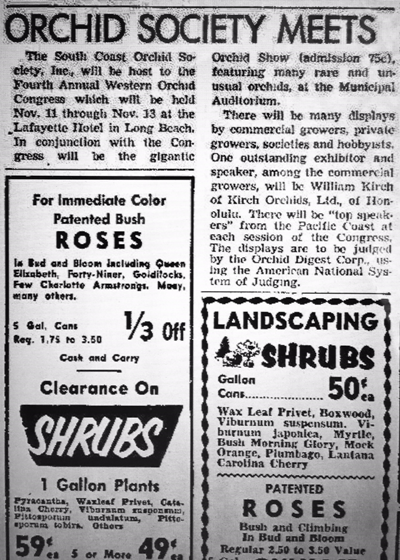

Pasadena Independent,

October 20, 1955, p. 97

Blast from the Past: 1955 South Coast Orchid Society was barely five years old when it hosted the Fourth Annual Western Orchid

Congress, November 10-13, 1955. SCOS was already meeting at 7:30 PM on the fourth Monday of every month, in 1952 at the Woodland Clubhouse in

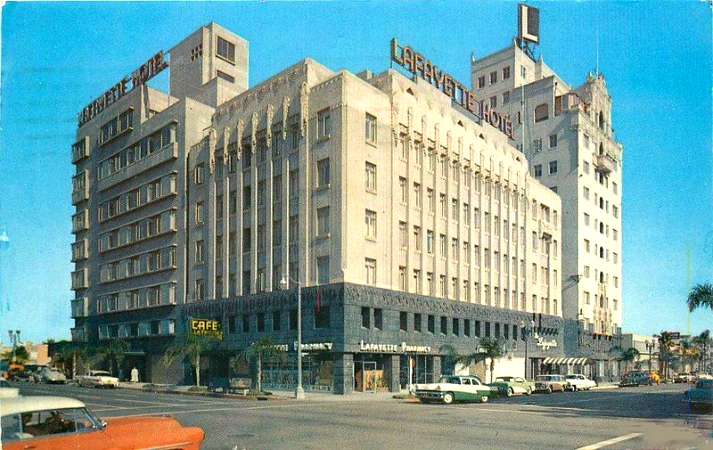

Recreation Park, and by 1955 at the Silverado Park Clubhouse. The headquarters for the convention was the venerable Lafayette Hotel at 140 Linden Ave.

in downtown Long Beach, now an apartment block. Admission to the exhibits and lectures at the Municipal Auditorium was 75¢. Presiding was

Morris Holmquist (Oscar Morris Holmquist, 1902-1990), a Long Beach realtor and developer,

but at the time apparently living in Artesia, who was active in the little group of orchid enthusiasts who were responsible for the organization of

various orchid clubs in Southern California. Holmquist served as President of the Orchid Society of Southern California in 1952.

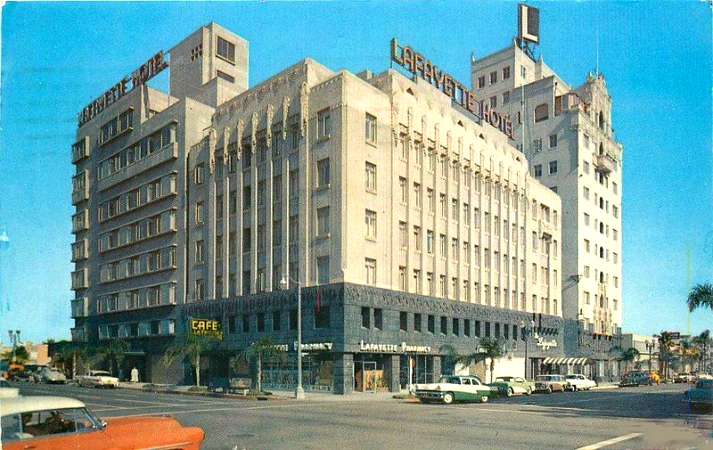

Lafayette Hotel, circa 1955

Lafayette Hotel, circa 1955

At the Congress in 1955, the first Orchid Digest Medal of Honor, an award of recognition for "Meritorious Service to the Orchid World", was presented to Robert Casamajor, first editor of Cymbidium News, who had been chairman pro tem at the 1946 organizational meeting of the Cymbidium Society. Casamajor (1885-1960) was active in many of the garden clubs in Southern California, including the Camellia Society, whose members formed the nucleus of the new Cymbidium Society. He has the distinction of having a Camellia, a Paphilpedilum (he was well known for his Paph hybrids and his cultural techniques), and a Cymbidium named after him.

The Long Beach Press-Telegram (November 7, 1955, p. 15) reported: "Orchid Care to be Shown Parley Here — Demonstrations and displays on corsage-making and potting and care of orchids will be held Friday at Municipal Auditorium as part of a four-day convention of the Western Orchid Congress. The show Friday, from noon to 10 p.m., will be open to the public.

"The congress will open sessions Thursday at 5 p.m. with a reception and social hour at convention headquarters, Lafayette Hotel. Morris Holmquist, Artesia, will preside.

"Special convention events include tours of the commercial orchid-growing establishments in the Long Beach – Los Angeles areas, meeting of the amateur growers, tours of amateur greenhouses and a banquet."

Long Beach Municipal Auditorium

(built in 1932, it was demolished

in 1975 to make way for the

Convention Center)

Both Holmquist and Casamajor were involved in the development of orchid judging in Southern California. John D. Stubbings (A Short history of American Orchid Society judging, Awards Quarterly, 18:90-91, 1987) noted that "in 1953, judging was expanded to include quarterly sessions in California headed by Morris Holmquist, Jay Muller, Robert Casamajor, Howard Anderson, and Etta Gray as a subcommittee of the COA" [Committee on Awards, renamed as the Judging Committee in 1996]. By 1955, as a result of developments at the First World Orchid Conference (St. Louis, 1954), a second edition of the AOS Handbook on Judging and Exhibition had been published, and an AOS regional judging center, meeting monthly, had been established in Los Angeles. Although we haven't tracked down the rest of the story yet, it appears that SCOS must have been involved in orchid judging under the Orchid Digest rules at that time, since the article in the Pasadena Independent seems to mention those rules. And it has been a very long time since we saw an orchid corsage, although we seem to recall that more than a few them were worn with the obligatory floppy Cattleya facing upside-down.

Ernest Hetherington (March 14, 2004, "Introduction", on the web site of the Cymbidium Society of America, Inc.), quotes Jack Hudlow, one of the founders of the Cymbidium Society of America who spoke in 1966 at a meeting of the Society in Pasadena, Californa, as follows: "Early in 1946, a small group of gardening enthusiasts (previously members of the Camellia Society) were invited to meet at the Pasadena public library with the purpose to 'initiate steps toward the organization of an "outdoor orchid society" '. These invitations, in the form of a letter, were sent out by Dr. David McLean. Prospective members were invited to bring a Cymbidium plant for the exhibit table. The organizational meeting was held April 3, 1946. At this meeting, the following persons were elected, pro tem: Robert Casamajor, chairman; Roy M. Bauer, secretary; and James Wright, treasurer. About forty members paid a $5.00 entrance fee..."

So far, we have not found any press coverage about the exhibits, the plants and their awards, or other activities held during the 1955 Congress. Please contact the web master if you have additional information.