October, 2019

Two common species of thrips: Thrips tabaci and Frankliniella occidentalis, highly magnified

Don't Blame Thrips and Raccoons for Everything!

Oddly, raccoons and thrips have something in common: they are rarely seen, but they can damage our orchids. However, it doesn't seem fair that they get blamed for the exploits of all the unseen culprits that trash our plants when we aren't looking. In all fairness, we have to rule out other causes. It turns out there is enough blame to go around.

Raccoons playing in the water plants at night

Raccoons really do get into mischief during the night. We have the trail-cam pictures to prove it! But there are many other critters who inhabit our Long Beach gardens. Shall we count the ways? Skunks, rats, squirrels, possums, cats, dogs, coyotes, rabbits... Did we miss any? We know they are around, because we occasionally see a live one in our gardens.

Rats in our orchid jungle gym!

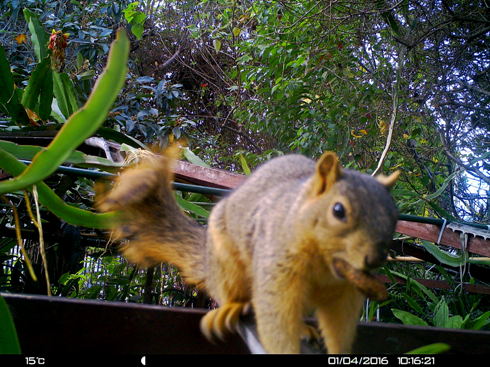

Squirrels definitely like to poke around our plants and occasionally nibble on them, but the other varmints are equally capable of gnawing, overturning, and otherwise destroying our plants. Most of this botanical vandalism seems to happen at night.

Squirrel with peanut, in our orchid habitat

It is tempting to try to trap or poison the offending critters. Here in California, the environmental dangers of traps and poisons have come to the attention of the public and the state government, with the result that our options for controlling unwanted critters are limited. This is especially true for what used to be called "rat poison": the most effective rat baits accumulate in the tissues of predators, thus endangering the whole food chain, as well as any of our pets who happen to be predatory. Our famous Los Angeles mountain lion called P-22 has had several run-ins with rat poisons, in spite of state-wide attempts to control those poisons.

Possum meets cat in the orchard

The poisons that remain available to the public are apparently not very powerful. Something in our garden seems to eat those baits on successive days for weeks at a time, as if some critter is getting fat off them. Even if we were able to eliminate the critters who live in our yards, there's nothing to prevent the neighbor's critters from taking their place.

Mountain lion P-22, famous resident of Griffith Park. Left, suffering from rat poison and mange in 2014; right, back in good health two years later

Long Beach is critter heaven. Our official city varmint is apparently the skunk, followed closely by the opposum, if we can judge from the ever-present road kill on our major streets.

Thrips on a the upper surface Plumeria leaf, photographed with an ordinary iPhone. Adult thrips are clearly visible, along with the damage they have caused, and some dust.

We don't often talk about thrips. Most of us don't know what they look like, have never seen one, and, worse, we lack the vocabulary. In hopes of clarifying the matter, we investigated. Thrips is a Greek word (singular) meaning something like "woodworm". As the "scientific" name of an insect, it is treated as a Latin noun (still singular). Because of the foreign origin of the word, the plural ought to be formed according to the rules for Latin nouns borrowed from the Greek, so the most likely plural would be Thripses. However, the dictionaries also recognize "thrips" as both singluar and plural in English. But that causes confusion in English when we have to talk about just one of them (although it can be argued that, in reality, they never occur singly); we can find "thrip" on the internet as the "alternative singular" of "thrips". Take your pick, and feel free to introduce thrip, thrips, or thripses into casual conversations with confidence.

The main problem with thrips, however, is that they are tiny. Many experienced orchid growers seem to blame thrips for just about any damage that can't immediately be attributed to some other obvious cause, without actually seeing the thrips. Contrary to what many people seem to believe, thrips are not microscopic! The adults are around 1 mm long — and they move! Think the thickness of a penny or a dime. They can be seen, and they can even be photographed with your cell phone. The immature forms are much harder to spot, because they are pale and nearly transparent. Thrips go through a series of molts before they reach the adult phase, and it is the immature forms that do most of the damage. The entire process, from egg to adult, takes around 2-3 weeks. However, if the infestation on a particular plant starts with just one batch of eggs, as seems likely, several generations will probably elapse before the damage is noticeable, and by that time, adults should be visible. Significant damage without the presence of adult thrips seems more likely to be the result of other causes.

Environmental damage on a small Cattleya flower: lots of tiny dust particles and scarring, but no thrips are visible. Probably due to ash particles. The damage appeared just a couple days after a major brush fire and Santa Ana winds.

Recently we noticed some damage to some little yellow Cattleya flowers. The scarring along the edges of the floral parts that touched each other looked just like the damage we saw on a Cymbidium at an orchid club meeting, for which the ribbon judge invoked thrips. We were curious — got out the 10 × magnifier (a souvenir from high school biology class). We saw minute dust particles, many of them black, but nothing that moved, and nothing resembling a thrip, live or dead. Our verdict? Fine ash from the fires, smoke, and Santa Ana winds that had blown through a few days earlier! Ash contains, among other things, corrosive metal oxides such as Na2O, K2O, CaO, etc., and any number of other combustion products. Add water, and you get lye.

Thrips on Plumeria leaf, iPhone photo. Note 4 pale, nearly transparent immature forms, marked with arrows.

Thrips seem to prefer other plants: They have attacked our Impatiens and Plumeria; the damage at first looked a bit like what spider mites do, but within a day or two, the adult thrips were easily seen.

Once we find thrips, what are the options? We tried pyrethrin-based sprays, which are about as safe as you can get, but they don't seem to be very effective unless every thrip is bathed in them. Systemic insecticides definitely work, but it may take a few days before the chemicals are absorbed by the roots and move up into the leaves where the thrips feed. There are a couple difficulties with systemic insecticides. Most of them are NOT safe for indoor use; they should not come in contact with your skin, nor should you breath the fumes or inhale the spray. Bayer markets a "2 in 1 Systemic Rose & Flower Care" that is easy to use, in the form of slow-release granules that are scattered around the base of the plant. This formulation seems to control sucking insects such as thrips, and also spider mites. However, the granules also contain a relatively small dose of 8-12-4 fertilizer. Just a light sprinkling seems to be enough to control thrips, scale, and mealy bugs on potted plants. Another systemic insecticide that has been recommended by some orchid growers is Safari, not usually available in California, and designed to be dissolved in water and sprayed on the plants or on the growing medium. If there is a biological control for thrips, we haven't found it. We prefer to try one of the pyrethrin formulations first. Our favorite is called "Home Defense" (thanks for the tip, Agnes!), available at Home Depot and elsewhere as a premixed spray. If that doesn't get rid of the bugs, then we can think about careful use of a systemic.

Bottom line here, let's be sure we really have a problem with thrips, before we bring out the strong chemicals.